As a photographer and creative, I felt an instant connection to the photographers and videographers in Gaza who were suddenly thrust into the role of PRESS after October 7th, 2023, wearing the blue vest and helmet for protection and identification, which has heartbreakingly not been enough to save so many journalists from being killed (over 100) and/or targeted.

Thanks to Instagram, I’ve been following multiple young journalists and storytellers who have been our eyes on the ground in Gaza for over half a year; creatives who have been heroically, desperately, and tirelessly (although they are very tired) sharing and pleading with the entire world for help, for ceasefire, for life, for freedom, for their native land. They are true heroes and leaders in my eyes, and I have been forever changed by their courage and their work.

I’m grateful that Salama Younis from Gaza is one of my newest Instagram friends (we “met” on December 1, 2023), and that we’ve been able to form a connection through photography, art, creativity and a desire for a better world for everyone.

In addition to discussing photography, Salama often shares that he expects to be killed, and how terrifying it is going to bed each night not knowing if that will be his last. “Do we sleep while we are waiting for death and a missile every moment? Haha, this is difficult. We don’t sleep, we fall asleep and wake.” What does one say to that?? I offer all the support I can through our translated messages, but sometimes my words feel feeble; I want there to be more that I can do.

Since Salama is one of the journalists documenting stories of those in Gaza – stories of love and loss, resilience and innovation, cries for help and messages of hope – I wanted to find a way to share a bit of his story with my community. I’m lucky enough that we have connected and that he has been open to sharing with me and answering my questions.

Our interview was conducted via text over Instagram. It is not as conversational as I would hope because I sent him a list of questions and then he responded when he could. I was able to follow up on a few of his responses, but of course there’s so much more I wish we could’ve covered.

Salama uses a translation app to read my messages and to translate his responses into English for me, which I didn’t even realize at first, so I really appreciate the extra effort that goes into communicating with me. And I also appreciate that technology has improved so much that hopefully it doesn’t make it too hard, either.

This interview contains his full responses; I have not edited anything except for a few bits of punctuation or spots where the translation needed some finessing. I hope you will enjoy learning about my friend Salama.

All photos with permission from Salama Younis (@salama_nabel on Instagram). Clicking on an image will either enlarge it or take you to the original Instagram post.

Salama’s GoFundMe page.

Interview took place from March 7-21, 2024

TB: Please introduce yourself, how old you are, where you are from (what part of Gaza specifically?), and your profession.

SY: My name is Salama Younis. I am 26 years old. I live in the Gaza Strip, specifically in the Nuseirat camp in the middle of the Gaza Strip. I studied at the university in the Faculty of Mass Communication, Department of Radio and Television. I work as a photographer and editor, and I work in the field of aerial photography. I also have a passion for film ideas in different fields.

TB: What inspired you to start learning and becoming a photographer and videographer? How did you learn/who taught you? (School? Internet? Practicing?) How long have you been doing this? Do you prefer photo or video?

SY: I have been practicing the photography profession since I finished my high school studies, as my cousin, who was martyred in our house during the bombing of my house, is the one who started with me in this profession, as he owned a photography studio. Accordingly, I registered at the university in the Faculty of Mass Communication, and based on my love and passion for photography, I was self-learning and constantly developing until I reached advanced stages in the field of photography and editing. I think I love making videos since [it involves] writing the idea, filming it, and editing it.

TB: I am so, so sorry that you lost your cousin. And I imagine you’ve lost many more people who are close to you. Do you want to tell me a bit more about your cousin? What type of photography did he enjoy? Was he photographing portraits in his studio? Did you work on film projects together? Do you have a photo to share of the two of you?

SY: There is a lot of work that we have done [together], including photographing a brand or photographing something in commerce and displaying it on social media, as well as documentation of large celebrations. He specialized in studio management, and he also had many ideas for photographing in a studio. He was also a middle school teacher in history.

TB: What equipment do you shoot with and edit on?

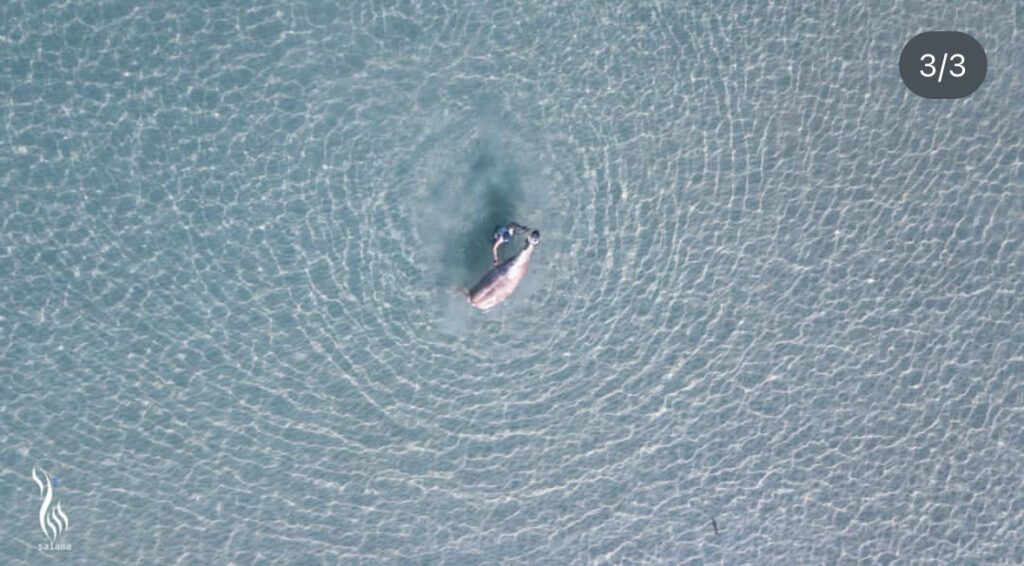

SY: I worked on Sony 2000 cinema video cameras, as well as Blackmagic and C100 cameras, and then I was creative in photographing large events with a crane device that was 12 meters long. After that, I was distinguished in photographing from the air using a drone to capture those wonderful and rare scenes from above Gaza, as the Gaza Strip lacks airports, as well as any type of travel, so I thought that photographing from above was like travel, even if it was through a photo, as I could see that freedom while I practiced it.

Then after that, I practiced editing and script writing in many institutions and production companies, where I won many awards in various competitions in short film making. I am trying intensely to develop in various fields of media.

TB: Tell me about one of your most memorable photo or video shoots. What made it special?

SY: That scene that I photographed while I was lying on the seashore, where the sea was without waves that day, and I photographed myself a scene while I was sleeping on the sand of the Gaza Sea. Where I felt absolute freedom at that time. Perhaps that scene was engraved and distinctive because I love sitting on the sand, love photography in Gaza, and I used to enjoy photographing that small spot and creating wonderful pictures from those places and trying to show my creativity in that small, closed place. That scene remained stuck in my mind and heart. In the background of the music, he says, “We are alive, but the dream remains.”

TB: Do you have a favorite place in Gaza to do photo/video?

SY: I believe that there is nothing but the sea in which we can find space for creativity. This is the least dangerous area. The profession of photography, and aerial photography in particular, is considered a dangerous profession by the occupation. As it is possible that the occupation will withdraw that [drone] with their advanced equipment or shoot at us. We lost a large number of photographic equipment during those chases.

TB: I have my own answer, but I’d like to hear in your words why you think the occupation considers photography and aerial photography to be so dangerous. When your equipment was destroyed, was it drone cameras that were shot out of the sky, or something else? Have you ever been attacked or injured while filming or photographing?

SY: Yes, photography via drone and from the air is a very dangerous matter. I was exposed to many situations in which I could lose my life. There is a lot of evidence. During the war, the occupation killed photographer Mustafa Thuraya and injured photographer Abdullah Al-Hajj. They worked in the field of aerial photography. It is a sensitive matter, and all types of photography are rejected by the occupation. The occupation does not want our voice and suffering to reach you, so it kills us.

TB: You work with (Palestinian filmmaker) Bisan, right? Can you share what it’s like being part of her team and the types of projects you work on together? Have you seen her or been working together at all since October 7th?

SY: I am basically a friend of that team. We create creativity and learn from each other constantly. But there was a program called Hakawatya presented by Bisan, and we were working with her to create that program, which was broadcast on the Jordanian Roya channel. My role in that program was an aerial photographer, as well as an assistant to them in ground photography, and I also stood with them since the team were my friends from the beginning, Dahman and Bisan.

TB: What has life been like for you since October 7th?

SY: I have to tell you something, that the injustice of the occupation did not begin [on] October 7th, since the occupation has carried out more than 5 devastating wars from 2005 until now, in addition to the siege it imposed on us for more than 17 years. But I think that before October 7th, I was establishing my life correctly, as only two days before that date, I finished completely building my beautiful house, as that work took years and money that I collected with difficulty. I was developing greatly in my work. Life for us was rosy, despite our limited means, but we loved life and sought to fix it as much as possible.

TB: I am absolutely heartbroken for you that you lost your brand new home that you’d worked so hard on. Do you have photos or videos of it? [Salama shared a few videos with me but they are not on his IG.] Also, you were about seven years old when you experienced your first war in Gaza in 2005? How has each war or attack impacted your life? I so admire you and everyone in Gaza for still being determined to make the most of life and to find joy.

SY: Yes, since childhood I have been in wars. Yes, there is no doubt that I have persevered and endured, but I am human and I do not expect that I am capable of sacrificing more than that. I am looking for any way to escape from this reality.

TB: Did you start immediately documenting what was happening, or did it take a while to begin?

SY: That took some time. Because I was in great shock. Because I want to tell you that I came out of a sudden illness that happened to me two months before the war. I entered intensive care and my condition was very, very serious. I began to recover a month and a half after the start of the war.

But then I immediately began documenting the crimes of the occupation. In all ways, starting with aerial photography, then I moved on to filming stories, as well as filming massacres, but I stopped filming by [drone] because it represents a severe danger and the photographer is exposed to direct targeting.

But now we are hiding in conveying these violations and the suffering of the people of Gaza to the world through our cameras and mobile phones, as well as through our pages, to try to make a change or convey our voice to that world.

[TB’s note: one of the stories Salama filmed that brought me to tears was about little Hammoud…and then the heartwarming follow-up story.]

TB: Your stories that you’ve filmed are how I connected with you, after Bisan shared one of them. How do you decide which stories to tell? Are you walking around asking people if they will let you interview them? Are people telling you about a special person or story to film? And, from a technical standpoint, are you filming and editing everything on your phone, or do you still have other camera and editing equipment?

SY: I do everything now using my mobile phone, photographing and editing everything. I do not have any photographic equipment. I personally request permission from the photographer, write the questions, direct the story on my own, photograph it on my own, produce it, and also send it to agencies that love these works. I try to do anything. I’m trying to get out of that reality, trying to keep working. I don’t know what to do, I’m powerless at everything.

TB: Have you traveled outside of Gaza? Where did you go? Did you have to get special travel documents? What was that experience like? And what was your travel experience like?

SY: Yes, I have Palestinian documents and a passport. There was one travel experience outside Gaza. I traveled to Turkey, where the institution that I worked with there offered me a trip to Turkey that rewarded my creativity in my work. The trip took less than a month. But I enjoyed it because I saw the world for the first time in my life as I was seeing the scenes from the drone, but I saw those scenes with my own eyes while I was above the clouds. They were shocking moments for me.

TB: How did it feel to travel on an airplane, what did you think? And to be in Turkey and to experience a different place – what excited you the most, and what surprised or shocked you the most?

SY: Everything I did once I left Gaza was amazing and surprising to me. I cried when I looked at the ground from the plane window and saw the sky above with my eyes, not my camera. Yes, I want to travel and see the whole world. I hope, that is my dream.

TB: Do you have a list of places that you’d like to travel? Or is that even something that you think about right now? In our early conversations we talked about how fun it would be to be able to photograph or film together someday – I won’t stop hoping for that, in whatever country where you can be safe.

SY: Yes, I am excited about the moments in which I benefit from your experiences in photography and working together, as well as going out together to photograph and practice what we love from our hobby and work.

TB: Do you think you will leave? If so, do you have family elsewhere, or where do you think you will go?

SY: I love Gaza very much. But the reality is difficult after the occupation bombed my home, my dream, and my place of work. I’m really thinking of traveling after the war ends, if we survive. But unfortunately I do not have a place outside Gaza, and I also do not have family outside Gaza. When the war ends, I will try to find a place that will welcome me to build my dream and my life again.

I am looking to get out of Gaza to Europe. Traveling requires money and needs people to welcome us. Things are very complicated.

TB: What is your dream for Gaza?

SY: My only dream is for the bloodshed to stop and for the people of Gaza to live in peace and security and in an independent and calm state. Because the people of Gaza love life, they are creative, they work hard, and they make life with their own hands.

TB: You’ve done a beautiful job of showing us the people of Gaza in your work – thank you. And I share your dream.

SY: Thank you very much from my heart for standing with me and supporting me.

TB: So many more questions, I know. I wish we could have a real conversation in person. Thank you, Salama, for taking the time to share about your life and to answer my questions. Is there anything that I didn’t ask about that you’d like to share?

SY: Thank you very much for everything. I am very happy to know you. I don’t know what I want to say, but I love living my life in a safe place in any way.

A few days after our interview, during one of our check-ins, Salama shared: “I know you are helping us with everything you have. I’m just pouring out what’s in my heart. Because when I die, I want you to know that I am a person who loves life and was successful in my life, but the occupation killed everything. When I die, tell everyone about me, that I was demanding my freedom and could not do anything.”

Salama is still in Gaza and we message regularly. He has a GoFundMe page if you’d like to support him and his efforts to rebuild his dream home. Please be sure to follow him on Instagram, as well.